1 – Introduction

2 – To Use or not to Use the Strict Chronology Version

3 – How Genesis Genealogies were Abridged

4 – Thread of History not Lost in the Post-Flood World

5 – Survival of the Genesis Chronology

6 – Writing and Technology: Did Mankind have to Start from Scratch?

7 – The Ice Age

8 – Conclusion

3 – How Genesis Genealogies were Abridged

In ancient times those who recorded and kept genealogies were not concerned that future generations would try to distance the formation of the natural world into a dim and distant past. First and foremost, they were historians, trying to record the highlights of their history; dates of events were also important, but not the primary concern. When compiling their genealogies, they weren’t thinking, “A few thousand years from now, the world will believe in vast evolutionary ages, so we’ve got to make sure our records are perfectly accurate and that we don’t miss a beat.”

Well there is evidence that they did abridge their genealogies to some extent and did “miss a beat” here and there. To understand this point, there is some rather startling evidence in the genealogy of Moses and Aaron.

In the Book of Exodus, the text states plainly, “And Amram took him Jochebed his father’s sister to wife: and she bare him Aaron and Moses.” (6:20) The strange thing here is that Amram lived during the early period of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt. He was the grandson of Levi, one of Jacob’s sons who migrated into Egypt at the behest of Joseph and Pharaoh.

Most likely, Amram’s father Kohath was already born when Jacob and his extended family moved into Egypt to begin the children of Israel’s 400-plus years sojourn there. Thus, if Kohath was a child at the time of migration into Egypt, then his son Amram and “grandson” Moses would have been born in the early stages of Israel’s sojourn there. That means Moses’ birth might have happened anywhere between 50 and 200 years after the entry into Egypt.

The Exodus took place 430 years after the Israelites’ entry into Egypt. (Exodus 12:40, Galatians 3:17) That means Moses, if he really was the first descendant of Amram and Jochebed, would have been anywhere between 230 and 380 years of age at the time of the Exodus. But Moses was only 80 years old when he led the children of Israel out of Egypt. (Acts 7:23,30)

So how do we account for this discrepancy? Here a little background understanding of ancient culture and language is helpful. The Hebrew word for “father” was somewhat vague and could easily be applied to a distant ancestor. And the word for “gave birth”, unless it was accompanied by the word for “conceive”, often meant something like “became the ancestor of”. When a genealogy does use the word “conceive”, then there is no question that the passage is referring to direct father-to-son linkages – no omissions of generations.

The genealogy for Joshua uses the word “conceive”, and he is recorded as having been born in the 10th generation of the children of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt – which, of course, suggests that Moses and Aaron should have appeared maybe in the 9th generation (rather than in the 3rd generation). (Read more about this in the Appendix 2 below.)

Besides the Amram-Jochebed “glitch”, there is also the statement that Amram had three brothers who all had children; and the total number of all the male descendants of Amram and his three brothers was 8,600 at the time of the census taken in the second year of the Exodus. (Numbers 3:1,19,27-28, Exodus 19:1) Thus, if Moses and Aaron were the immediate sons of Amram, then we would have to believe that the two brothers had 8,600 male relatives (mainly cousins and nephews and a few uncles) all descended from their “grandfather” Kohath.

Evidently, Moses and Aaron were not the immediate grandsons of Kohath nor the immediate sons of Amram and Jochebed but were born a few generations later. Thus, the text in Genesis 6:20, which states, “Jochebed… bare him Aaron and Moses,” should be understood as saying, “Jochebed… bare him the ancestor of Aaron and Moses.” Or “Amram and Jochebed originated the family out of which came Moses and Aaron.” This idea of a person “giving birth to a family” appears more plainly in Numbers 3:27, “And of Kohath was the family of the Amramites.” And in the mention of Moses’ birth parents: “a man of the house of Levi went and took as wife a daughter of Levi.” (Exodus 2:1)

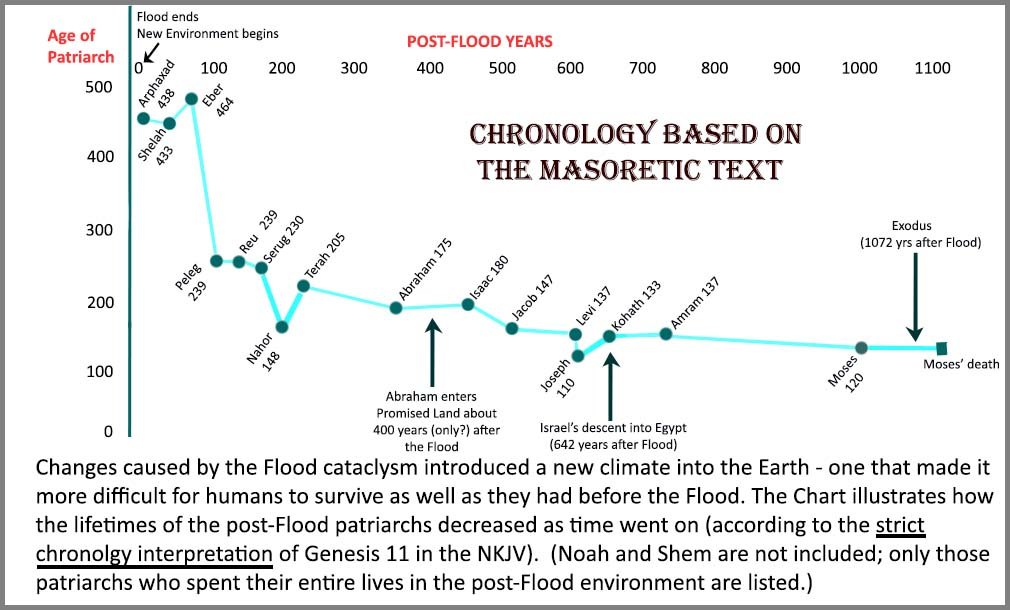

The dates used in the above Chart are based on the genealogy given in the Masoretic Text

The dates used in the above Chart are based on the genealogy given in the Masoretic Text

Perhaps in those obscure years of bondage, without much self-government, the children of Israel had less incentive to keep records. During this time when the people were pre-occupied with their slave labor, distracted and disorganized, the task of record-keeping may not have had much priority. And very likely, with less established leadership or clear line of succession in their society, and because of the large population, it was difficult for the Israelites to keep track of the “who” or the “when” amidst the multitude of births of that era.

“The children of Israel were fruitful and increased abundantly, multiplied and grew exceedingly mighty; and the land was filled with them.” (Exodus 1:7)

However, even though the length of Israel’s sojourn in Egypt cannot be reckoned via the genealogies, we do know the time span from the statement in Exodus 12:40-41, “And it came to pass at the end of the four hundred and thirty years, even the selfsame day it came to pass, that all the hosts of the LORD went out from the land of Egypt.” (KJV; also Galatians 3:17)

Another similar period of history is recounted in the Book of Judges: “In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” (Judges 21:25) Again, because of the lack of organization and clear line of succession during that era, genealogical records do not appear in the Book of Judges. Not until a thousand years later do we learn about the length of that time span when the apostle Paul, while recounting Israel’s history, stated, “He gave them judges for about four hundred and fifty years, until Samuel the prophet.” (Acts 13:20) Paul, an educated man, knew a good deal about Israel’s history, so he was able at least to give an estimation of the length of time for that ancient era.

But it is only an estimation: “about four hundred and fifty years.” To expect exact, total accuracy in Biblical chronology would be a futile exercise. But we can expect approximate accuracy, and that, along with all the scientific evidence, is enough to validate the authenticity of the Genesis record and its account of a definite beginning of the natural world and of human history. (For “scientific evidence”, refer to the posts in Retrieving Our Lost Heritage, or any of the several Creationist websites that are available.)

It is remarkable then, to see how God was able to keep up with the record-keeping. He provided the time span summaries for those eras when His people were not able to keep up with their record-keeping.

Continuing with the story of the birth of Moses and his mother’s courageous efforts to preserve his life, we can note that the text makes no mention of her name. (Exodus 2:1-9) And probably the reason for that was that she was not the Jochebed who married Amram. But she was one of their descendants.

This example of Moses’ “birth” parents shows that sometimes ancestral forefathers were named, while the immediate or intermediate fathers’ names were omitted in the Genesis genealogies. Such omissions happened, it seems, when the population was growing rapidly and before the people of God began to live as an organized community.

When Israel became structured as a nation, then began an unbroken and detailed recording of the comings and goings of generations of kings and ancestors. In the absence of that kind of historical-cultural setting, however, the tendency in the recording of genealogies was to mention only the names of prominent or pivotal personages, leaving some of the less notable (but not necessarily less worthy) ancestors unmentioned.

Another related topic is the glaring difficulty concerning the problem of how to explain the very short time span between the Flood and the arrival of Abraham. If we are to go strictly by the chronology given in most modern Bibles, then we would have to believe that, only 400 years after the Flood, Abraham was traveling through lands already established with civilizations, pyramids, etc.

The Bible implies that the world of Abram’s day, with its civilizations and cities, was ancient already; and we are left with the unmistakable impression that its peoples had long since been divided “after their families, after their tongues, in their lands, in their nations” (Gen. 10:5, 20, 31).

As we follow Abram in his wanderings, from Ur of the Chaldees to the land of Canaan, filled to overflowing with “the Kenite, and the Kenizzite, the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Girgashite, and the Jebusite” (Gen. 15:19-21); and then follow him down into the land of Egypt with its Pharaoh and its princes (12:150); and then see him going to Lot’s rescue in the vicinity of Damascus after Lot and other captives from the five Cities of the Plain had been deported by the kings of Shinar, Ellaser, Elam, and Goiim (14:1-16); and then see him being met by a priest-king of Salem (14:18) and Hittite landowners (23:2-20), we cannot help but feel that [a good amount of time had passed since the Flood, more than what can be outlined in most modern Bible translations].

(The Genesis Flood, pgs. 478-479. Published 1961)

Furthermore, we should consider what Genesis 10:25 states: “And unto Eber were born two sons: the name of one was Peleg; for in his days was the earth divided.” According to a strict chronology interpretation, it wasn’t just Peleg who was alive when the earth was divided. There would have been also Noah, Shem, Arphaxad, Shelah, and Eber. Yet the phrase (“in the days of Peleg”) gives the impression that Peleg was the only patriarch around in those days when “the earth was divided.”

And then to top it all off, according to the strict interpretation, the patriarch Shem would have been alive during the lives of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Yet there is no mention at all of this extraordinary fact in the detailed stories of those three patriarchs. The inescapable conclusion: Peleg’s ancestors had already passed away.

If the strict-chronology interpretation of Genesis 11 is correct, all the post-diluvian patriarchs, including Noah, would still have been living when Abram was fifty years old; three of those who were born before the earth was divided (Shem, Shelah, and Eber) would have actually outlived Abram; and Eber, the father of Peleg, not only would have outlived Abram, but would have lived for two years after Jacob arrived in Mesopotamia to work for Laban!

On the face of it, such a situation would seem astonishing, if not almost incredible…

(The Genesis Flood, pgs. 477. Published 1961)

Interestingly, the Greek Septuagint Bible allows for a span of well over 1,000 years between the Flood and the birth of Abraham. And this seems more realistic, if for no other reason than the fact that those who translated the Septuagint lived closer to that ancient historical era and had a better knowledge of what happened before their time and how long ago it was; and importantly, they would have had access to very ancient manuscripts.

Another version of the Hebrew Torah (first five Books of Moses), the Samaritan Pentateuch, was formulated in about 100 BC and agrees with the Septuagint Bible. Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian of around AD 100, also uses in his writings the same ages that are given in the Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch Bibles.

Nowadays, we use the Hebrew Masoretic Text for Bible translations of the Old Testament. But it should be kept in mind that it was formulated in 1008 AD, and the manuscripts the Jewish scribes had access to were not nearly as ancient as those used for the Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch. And there is some question also about the trustworthiness of the Jewish scribes who worked on the Masoretic text. Generally, where there is a difference between what the different texts say, it is safer to prefer the Septuagint or Samaritan Pentateuch versions.

A video, called “Were the Pyramids Built Before the Flood?” by Nathan H83, offers more information about this issue and is well worth viewing.

Regarding the patriarchs’ ages at the birth of their sons, the Septuagint translators have been accused sometimes of tampering with the text. The ages given for most of the patriarchs have an extra 100 years more than what is given in the Masoretic Text. So the question is, did the Septuagint translators add these extra years, or did the compilers of the Masoretic Text snip off 100 years from the birth times of the patriarchs’ sons?

Here is one way to look at it: In the post-Flood era, the atmosphere could no longer protect humans very well against the Sun’s harmful radiation (cosmic, UV, and x-rays) which cause aging. That would mean that if a person, genetically, was prone to live for 100’s of years, chances are that their old age would be quite difficult (after having been exposed so long to the Sun’s radiation).

The post-Flood environment would favor then those people who had a genetic predisposition to mature physically at an earlier age and have a shorter life span. Thus, they would not have to endure a lengthy and difficult decline in their old age; and also, it would be easier for them to raise a family. The patriarch Isaac, for example, lived a lengthy 180 years, but much of his old age was spent in blindness; as a result he found it difficult to manage the affairs of his sons Jacob and Esau. (Genesis 27)

In the pre-Flood Age, people lived about 900 years; in the post-Flood Age, lifetimes dwindled down, eventually, to an average of 70 years (according to Psalm 90:10). We could look at the example of the pre-Flood patriarch Seth, son of Adam, who died at the age of 912. According to the Septuagint, Seth had his first son at the age of 205. This might seem “old” to us. But in a lifetime of 70 years, this would be the equivalent to 16 years of age. At 205 Seth’s physique could have had the same maturity, in modern times, as that of a young man of 16. But if Seth were living in the post-Flood Age, at 205 years his health might have suffered and made it difficult to start raising a family.

Perhaps this is speculating, and it is assuming that the rate of maturity in a long life of 900 years would be much slower than the rate of maturity in a shorter life of only 70 years. But it doesn’t seem unreasonable to think that.

According to the Masoretic Text, Seth had his first son Enos at the age of 105 years. The equivalent in a lifespan of 70 years would be 8 years of age. Looking at it from this point of view, the Septuagint version of the patriarchs’ ages seems more sensible than those in the Masoretic Text.

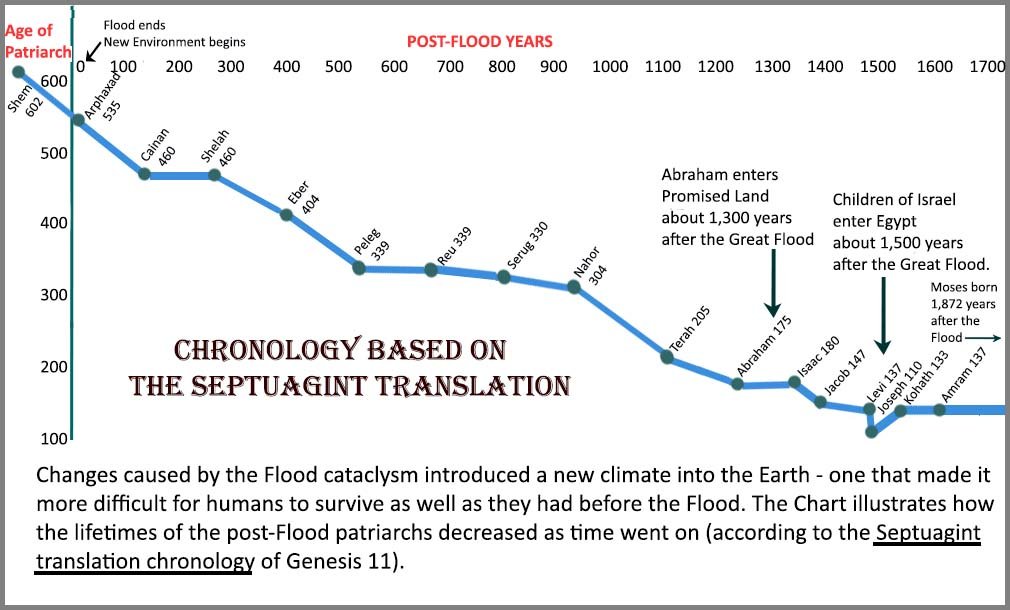

Another peculiarity that shows up in the Masoretic text is the huge difference in ages between Eber and his son Peleg – 225 years! In the Septuagint, that difference is only 65 years. The Charts below show the timelines plotted from the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint translation. By comparing them, it is easy to see that the Septuagint shows a more realistic, historical outline of the post-Flood genealogy.

A note about the above Charts: Until the arrival of the patriarch Abraham and his sons Isaac and Jacob, there is hardly any record of the life stories of those who came before. The years after the Flood were a time of migration, exploration, and population growth. There is a possibility then that the genealogy of this pre-Abraham era omitted some generations, just as the genealogy between Amram and Moses, in the pre-Exodus era, missed some generations.

Some patriarchs could have been the founders of a family that included one or more generations not listed in the Genesis genealogy. But other than this, there is a remarkable chain of unbroken links that can be traced through that early post-Flood, pioneer stage of migration throughout the Earth.

In these modern times, we like to be very specific and exact with our dates and times, and we have the technological means to do so. The people of ancient times could be very exact and precise also, at least when it came to practical affairs. Money, weights, volume, size measurements were important in trading and building enterprises. But where it had to do with the passage of time, there was less concern about accuracy.

They may have felt it was more important to make sure the sacred records (the Creation and Flood accounts) were passed on from generation to generation, and the genealogies were a secondary consideration. And to aid in the transmission of those sacred records, it was helpful to make certain shortcuts and stylistic changes to the less engaging aspects – those tedious genealogies.

Since the records were to be treasured by future generations, there was a different perspective as to how to present the various numbers and ages and so on. There was a concern for numeralogical symmetry, along with a preference for certain auspicious numbers. To them the task was an artistic one; exactness and accuracy were more of an afterthought.

The ancient compilers may have had what seems to us an odd, skewed perspective on how to assemble chronologies. However, that does not mean that the Biblical record should be discarded. Nor does it mean that the timeline of history can be stretched very far beyond the strict chronology given in the Bible (or in other non-Biblical sources). The reasons for this will be made clear as we go along.

***

Appendix 2: Joshua’s Genealogy

In 1Chronicles 7:20-27 we find a listing of the generations from Ephraim (grandson of Joseph and Rachel) to Joshua. Verses 23-27 show that Joshua was the 10th descendant. In this passage (verse 23), besides the usual word for “beget” or “bear” (yalad ), the word (harah) for “conceive” is also used. (“She conceived and bore a son” NKJV; “became pregnant and gave birth” in NIV) When these two words are combined like this, it removes the usual ambiguity, making it clear that the passage is describing this as a direct father-to-son lineage.

In the case of Moses and Aaron, however, the word for “conceive” is not used in Exodus 6:20. And the lineage after Jacob is expressed as going from Levi to Kohath to Amram to Moses. This makes Moses the 4th generation after Jacob, in line with the statement in Genesis 15:16, “In the fourth generation they [Abraham’s descendants] shall return here [to Canaan].”

Although, strictly speaking, that is not correct, it seems that, unless specified with the word “conceive”, then in the language and culture of that ancient time, those words “fourth generation” could be interpreted rather loosely (according to our modern way of thinking). To be exact however, since Moses was born in the generation before Joshua, then he should have been approximately the 9th, not the 4th, descendant after Jacob (since his protégé Joshua was the 10th descendant).